A classic Hollywood tale: a team of humble beginnings uses grit to snatch victory from unbeatable goliaths. Why do people enjoy a good underdog story? One USF study found that one reason people cheer for the uphill battle is to prove that the world is just. Despite one team having more money, or happening to bogart all the talent, people want to believe that there is still a chance for others to compete and win. Another hypothesis is that people are gaming the emotional outcomes: if you root for the big dog, and its expected to win, the joy isn’t very substantial. If you support a team that has all the odds stacked against them, and they pull off a victory–it’s time to crack out a high-five that’ll wake the dead! So where does the underdog story take place in tennis?

Data

I looked into data from the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) that documented matches from 2012 to 2017. This contained information on tournament matches round by round with betting odds from several websites including BetOnline365.

I defined an upset as the player winning with a lower win probability (the betting odds gave a bet on them a higher payout, and a lower chance of winning). An expected outcome is the opposite: the more likely to win succeeded.

Circumstances

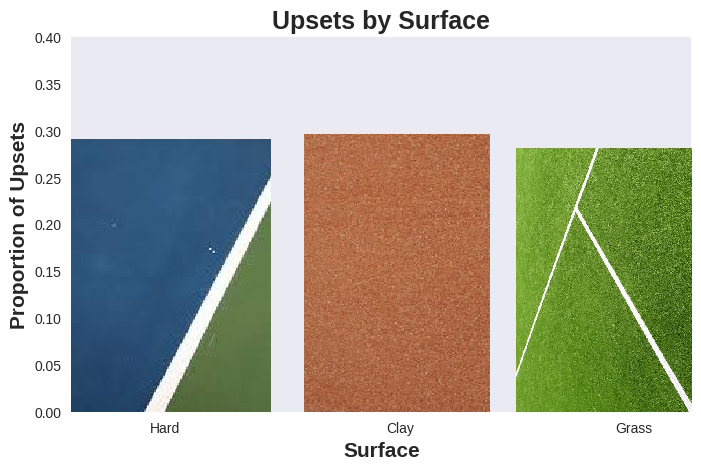

First, I looked at surfaces. Tennis is most commonly played on three types of courts: hard, clay, and grass.

For all these surfaces, just under 30% of matches played ended in an upset. The upsets per surfaces were not different enough to make a substantial claim. A bit of background: hard court is the standard, it’s played for most of the year. Clay is the most inconsistent surface, bounces can be erratic and unpredictable. Grass court tournaments often have their own unique seeding system so the players that are better on grass are already seeded higher. It’s also the shortest season of the tennis year.

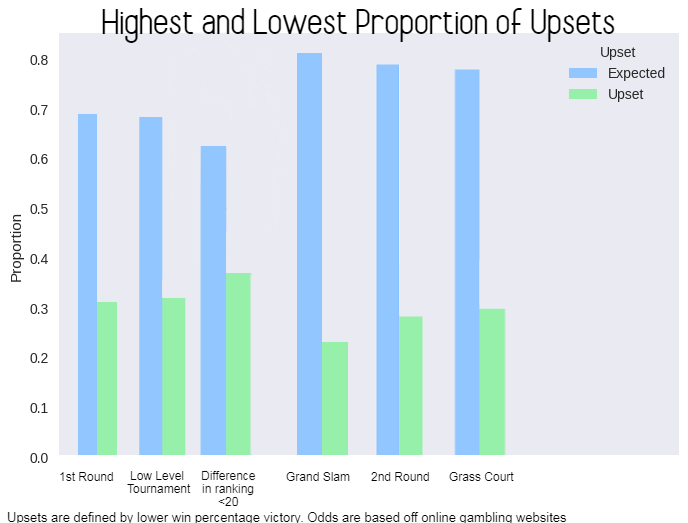

After sifting through multiple variables, I gathered the conditions that led to the most and least upsets.

The first round is prime territory for someone to break ahead and play exceptionally well. Next, in lower level tournaments players might be coming back from an injury or maybe a good player is trying to get over a cold streak. For the low upsets, a grandslam is particularly difficult to have a heroic run because the matches are much longer–you spend a lot more energy on court, and it’s tough to sustain that. That’s why the 2nd round is there as well, after one lucky break, it’s difficult to keep it going.

Players

Next I looked to see which players produced the most underdog victories.

| Player | Expected | Upsets |

|---|---|---|

| Benoit Paire | 80 | 57 |

| Joao Sousa | 56 | 53 |

| Marcel Granollers | 57 | 51 |

| Guillermo Garcia-Lopez | 74 | 49 |

A player capable of a lot of upsets isn’t necessarily the most clutch; they can’t get there without being the underdog in the first place. They’re a player that is often fighting from the middle ranks, but has a lot of potential. Probably a player with lots of hot and cold streaks, Benoit Paire is exactly this player.

No sane person would have attempted the following shot with the match hanging in the balance. Any normal player being of sound mind and body would let it bounce, go for the half volley, and look to defend from there. Not this frenchman–he had an attacking gameplan from the start of that serve and was determined to pull off something spectacular. It’s this aspect of his mindset that has defined his career: percentages mean nothing to this man, and instead of playing it safe and feeling out opportunities (which by the way is exactly how his opponent this match plays), he’ll commit to shots that no one has any business making. And his career has followed suit: when he’s on, he can pull off the mesmerizing, but when he’s off, you’ll wonder what happened to him. It’s a hot-lava and cold-iceberg situation that plants him squarely on the unpredictable side.

Fit a model

Based on which round it was, which level of tournament, and the differences in ranks I fit a model to predict upsets. The model was able to explain 27% of the variation in upsets. I’m not packing up and running off to Vegas with this information (in part because you can gamble online) and betting it all on a model that only explains 27%. Clearly, the people running the betting websites have access to vast data, and have accounted for much much more in their odds. But perhaps this is something to consider and fit into a larger, more sophisticated model. Knowing which round, tournament, and the difference in rankings, could influence the optimal betting strategy. Or just knowing which Benoit Paire shows up that day.